Three unique psychosocial adaptation clusters characterize MPN patients

Living with a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) presents psychosocial challenges due to its prolonged course, symptom burden, and uncertainty about progression. Despite similar clinical profiles, patients differ markedly in quality of life (QoL), reflecting distinct psychosocial adaptation patterns. Key variables—coping, resilience, and illness identity—strongly influence well-being. Notably, ‘engulfment’, i.e. the feeling of being overwhelmed, predicts poorer QoL [Eppinbbroek et al., 2024]. This study applied cluster analysis to identify psychosocial adaptation profiles in MPN patients and examined differences in sociodemographic, disease-related, self-management, symptom burden, and QoL outcomes over time.

This longitudinal study included 338 Dutch MPN patients recruited via patient organizations and online platforms. Participants completed identical online questionnaires at baseline (T1) and six months later (T2). Variables included coping (SPSI-R), resilience (BRS), and illness identity (IIQ). Comparisons between psychosocial adaptation clusters were made on sociodemographic, disease-related, self-management (PAM-13), MPN symptom burden (MPN-SAF TSS), and QoL (EORTC QLQ-C30) variables. Cluster analysis (Ward’s method, K-means) identified psychosocial adaptation profiles derived from T1. Subsequent chi-square and ANOVA tests examined group differences, and Δ-scores assessed longitudinal stability. Ethics approval was obtained (Open Universiteit, 2022; OSF preregistration).

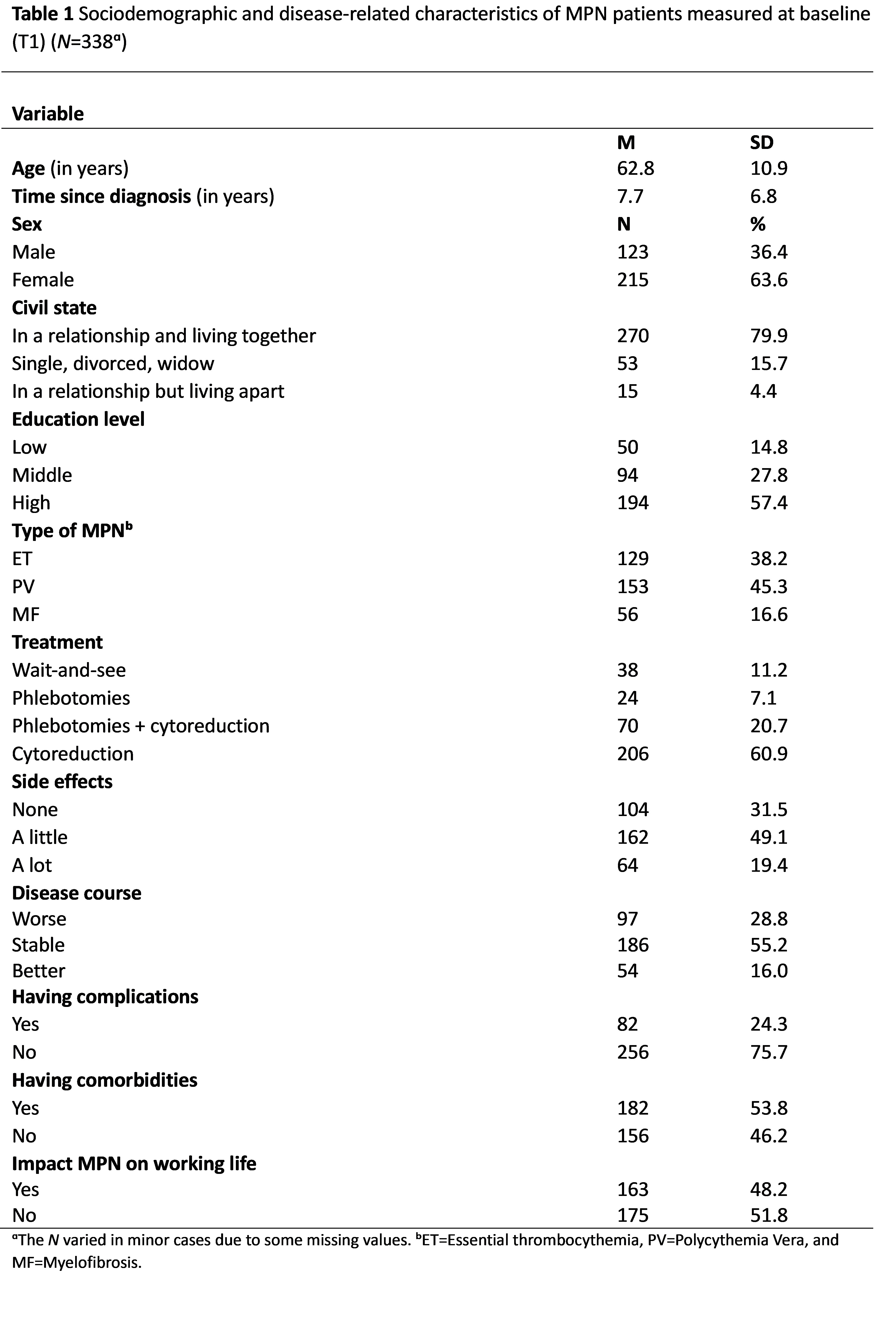

63.6% of the participants were female and the mean age was 62.8 years (SD=10.9). Most were highly educated (57.4%), in a relationship (84.3%), and diagnosed with polycythemia vera (45.3%). Cytoreduction was the most frequent treatment (60.9%), with side effects (68.5%) and comorbidities (53.8%) common (table 1).

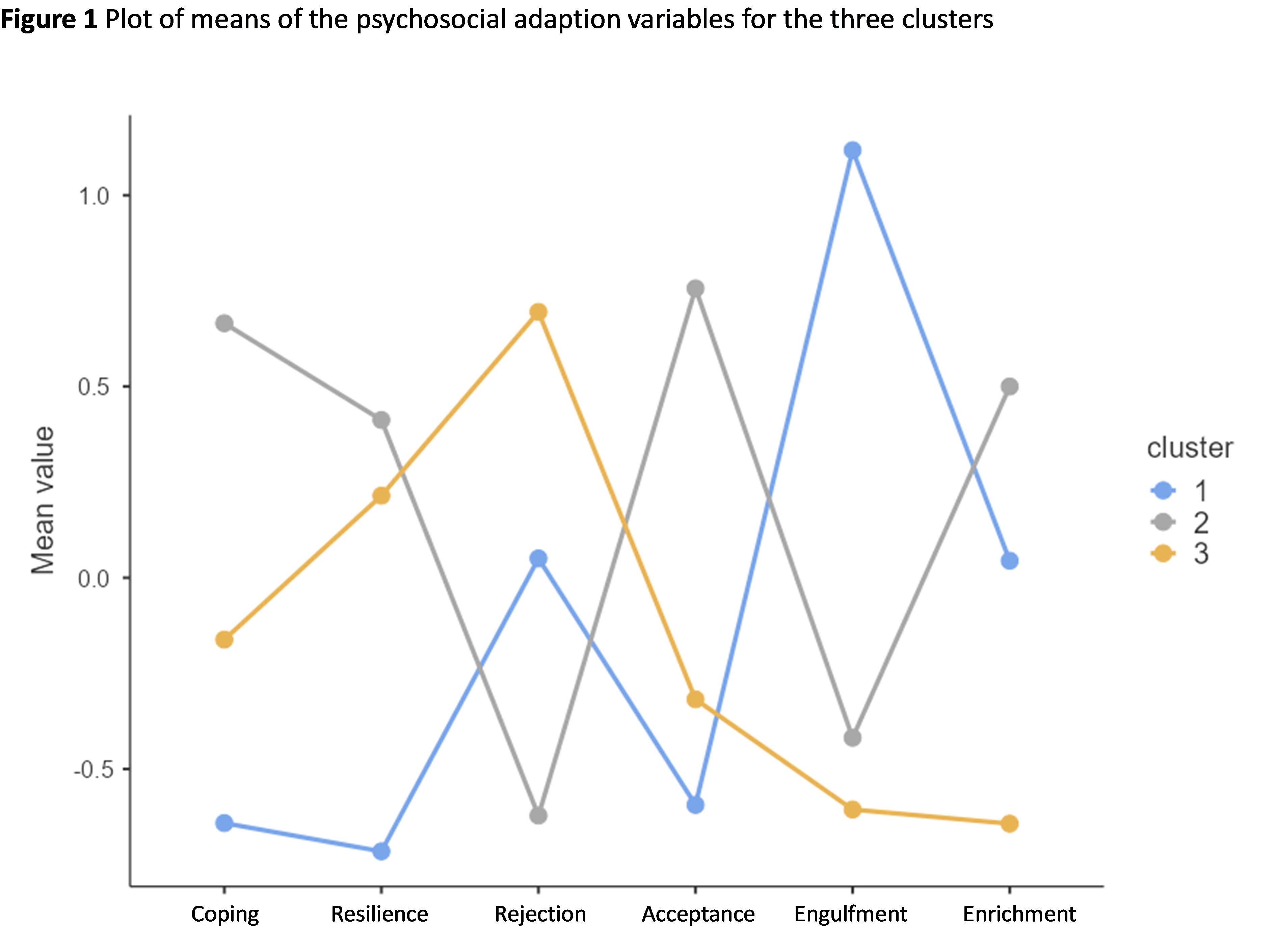

Cluster analysis identified three distinct psychosocial adaptation profiles, as showed in Figure 1.

· Cluster 1: Poor Adapters (N=105)— high disease burden, lower education and low adaptation (coping and resilience, high engulfment, and poor acceptance).

· Cluster 2: Well Adapters (N=127)—longest disease duration , strong self management and high adaptation (high coping, resilience, acceptance, and enrichment, with low engulfment and rejection).

· Cluster 3: Active Distancing (N=106)—oldest patients with low illness identity (high rejection, low engulfment and enrichment)

Clusters differed significantly in education, age, and disease characteristics. Poor Adapters were younger, less educated, and reported more comorbidities, side effects, disease deterioration, and work impairment. Well Adapters had the longest disease duration and highest self-management, while Active Distancers reported fewer side effects, comorbidities, and disease impact. Poor Adapters had the highest symptom burden, fatigue, and insomnia, and the lowest QoL and functional scores.

Over six months, no significant changes were observed in outcome variables. Regarding cluster variables, Poor Adapters significantly improved slightly in coping and reduced engulfment. These findings confirm heterogeneous psychosocial adaptation patterns in MPN, with implications for personalized psychosocial interventions.

Identifying these profiles can help tailor care, with special attention to poorly adapting patients who experience the highest burden, underscoring the importance of targeted psychosocial support and interventions to improve their daily functioning and well-being.